By Ted Murphy

Doug was recently recogonized at the Arcanum’s Purple Heart Ceremony September, 2022. Posted in honor of upcoming Veterans Day in November.

Whenever I’m in Washington, D.C., I visit Doug. He’s always at the same place and you can find him there too. Just go to panel 16 W, line 034 at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial (the Wall) and you’ll find him: DOUGLAS PAUL LEFEVER the only Arcanum serviceman killed in the Vietnam War.

Every time I look up at his name on that boundless, black granite wall, two thoughts go through my mind. I bet Doug doesn’t get many visitors; and I wonder if people still remember him? And that’s why I set out to learn more about Doug and tell his story.

40 years ago this month, in the early morning hours of November 5, 1969, Captain Douglas LeFever was at the controls of an F4D “Phantom” fighter-bomber knifing through the pitch-black darkness at 10,000 feet above the Mu Gia Pass in Laos. Along with his back seat co-pilot/navigator Captain Joseph Y. Enchanis, Doug was on a Fast FAC (Forward Air Controller) mission to locate enemy targets, mark them with white phosphorous 2.75-inch rockets, and then direct other aircraft to the targets.

That morning, he controlled two Navy A-6 “Intruder” attack aircraft, call signs “Streetcar 302 and 304.” They were “holding high” at 12,000 feet with their navigation lights off waiting for clearance from Captain LeFever to launch an air strike against the heavily defended Ho Chi Minh trail, a primary route the enemy used to move men and supplies from the North into South Vietnam.

According to battle reports, the weather was marginal and cloud cover was heavy. At 4:36 am, Captain Lefever, call sign “Owl 15,” fired three rockets to mark the target area, dove down and rolled-in through the clouds to continue his attack.

Suddenly the Navy bomber pilots heard a “Mayday” distress call and saw a bright flash. The clouds below them lit up with a large explosion, and their radio calls to “Owl 15” went dead. Like a shot, the Navy pilots dove down to 6,000 feet beneath the clouds to find the crash site, but saw no fires in the heavily forested mountainous area and heard no emergency electronic signals. SAR (search and rescue) operations were carried out for 13 ½ hours, but the heavy jungle canopy and rugged terrain where “Owl 15” went down were so impenetrable that a visual search was impossible. No wreckage was ever found.

No one knows what happened. “Owl 15” could have been struck by a SAM (surface to air missile), hit by enemy anti-aircraft guns, or flown into one of the fog-shrouded mountains surrounding the Mu Gia Pass.

What we do know is that for 26-year old Captain Douglas Paul LeFever of Rural Route 3, Arcanum, Ohio, time stopped on this–his 155th–and final combat mission. While listed as MIA (missing in action), Doug was promoted to the rank of Major, and then officially declared as “killed in action” by the Department of Defense in 1978.

Growing Up

Doug was the only child of Paul and Thelma LeFever. He spent his early years on a farm on Winnerline Road east of Route 127, north of Eaton, OH and attended Monroe School. In 1957 the family moved to a 169-acre farm on the Otterbein-Ithaca Road, which is today the Lee Jackson farm. Doug went to Arcanum High School his sophomore and junior years, and then returned to Monroe Central in Preble County for his senior year, graduating in the class of 1961.

“Doug and I were best of friends through Monroe and at Ohio State,” said Al Snyder of Davenport, FL. “He was someone I always looked up to; level-headed, considerate of others, and serious about his life and faith. In high school, he was very active in the F.F.A. (Future Farmers of America) and kept excellent records on his corn and soybean crops, one year winning the F.F.A. State Farmer Degree, which was very tough to get.

“I remember that on high school weekends after we took our dates home, we’d meet up late at night at the Sunset Lanes bowling alley on Route 40 and get hot cinnamon rolls fresh out of the oven. We solved a lot of the world’s problems over tall glasses of milk and cinnamon rolls in those days,” he added.

“When I heard…that Doug had been shot down and was missing in action, I was heartbroken,” said Snyder, “But he was a very resourceful guy and I always held out hope he would…escape and make it home, but that was not to be.”

At Ohio State Doug played on the lacrosse team, was vice-president of Delta Theta Sigma, a professional fraternity, and graduated in 1965 with a degree in agricultural economics.

He was also commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the Air Force Reserve through the Ohio State ROTC (Reserve Officer Training Corps) training program.

“Doug started taking flying lessons through ROTC at Don Scott Field while we were at Ohio State,” said his college roommate Phil Gillespie of Sebree, KY, who named his first son after Doug. “He really wanted to fly, and always had a goal to take his Dad flying. After completing flight school and before his first tour in Vietnam, Doug came home to spend some time with his folks. One afternoon, he went to the Phillipsburg airport, rented a small Cessna 150, and took Paul up for a flight. Doug was so proud he was finally able to do that for his Dad, and I know it was a very special memory for both of them.”

During his first tour of duty in Vietnam, Doug was a back seat co-pilot/navigator in the F4D “Phantom.” In January 1969, he returned to MacDill AFB in Tampa, FL for upgrade training to aircraft commander. “Doug told me he didn’t enjoy flying in the back seat. Like all true fighter pilots, he wanted to be in the front seat as the aircraft commander,” added Gillespie.

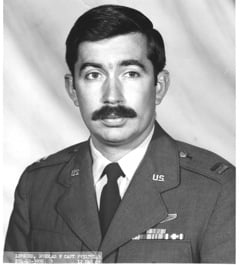

While at MacDill, Doug dated a young air force nurse, Lt. Paulette Hughes from Lynchburg, OH. “Doug was very handsome and confident and I was a bit in awe of him because he was a Captain, a fighter pilot who had been overseas,” said Hughes. “Like many war zone pilots, he had a big mustache because there was a superstition that it would make them “bullet proof.” We were a good fit, both of us were Ohio farm kids who enjoyed the Tampa beaches and Doug sure could make an excellent Bloody Mary. Sadly, I remember that just before he left MacDill to return to Vietnam, he confided that he didn’t think he’d be coming back,” she added.

Finding Doug

Although Doug spent his high school and college years just a mile down the road from the farm where I grew up, I didn’t know him well. I found much of his story in a Sutton’s grocery bag in the closet at the Otterbein-Ithaca Road home of Bill Brown, who is Doug’s cousin and primary next-of-kin.

Reading through Doug’s records, I saw that he listed three familiar Arcanum names as character references: John A. Kay, Harold (Timmy) Smith, and Deo Troutwine. I also discovered that his combat commanders thought he was an exceptionally fine officer. Some reported he was: “extremely steady and effective even under the most adverse conditions,” “one of the hardest working and most conscientious officers in the squadron,” “his coolness under fire is remarkable,” “highly professional, takes great pride in seeing a job well done,” and “in the top 10 percent of all pilots.”

The vast majority of people who serve in the armed services never experience the terror of combat. My Dad saw more than his share of action as a combat infantryman fighting across France with the 90th division in World War II. He never talked much about it, but I remember one night, many years ago, driving across Florida after the Daytona 500. He just opened up. “Most people don’t understand what it’s like to go through combat, to constantly live in danger, and know that the enemy is doing everything they possibly can to kill you,” he said.

Doug LeFever knew well the hazards of combat. Flying a high performance fighter jet in combat is one of the most dangerous and demanding jobs in the world. During his two tours of duty in Vietnam he racked up a staggering total of 155 combat missions with the 497th Tactical Fighter Squadron, “The Night Owls,” flying out of Ubon, Thailand.

The “Night Owls” flew their missions only at night and suffered heavy combat losses. The squadron’s F4D “Phantom” fighters were armed with the latest “Paveway” laser guided precision bombs, and Doug played a major role in the development and tests of the new weapon system. Since they worked in high-threat areas and flew low to draw-out enemy fire, their Fast FAC (Forward Air Control) missions were some of the longest, most difficult and dangerous missions in the war. In fact, one estimate was that pilots flying Fast FAC missions were 25 times more likely to be shot down than pilots flying regular combat missions over enemy territory. During the war, 338-air force FAC’s were lost in the skies over Southeast Asia.

To understand what these missions were like, imagine yourself at the controls of the “hottest” fighter-bomber in the world. The F4D “Phantom” is a massive aircraft costing two million dollars (in 1968). It is 62 feet 11 inches long, carries up to 18,600 pounds of weapons, and can reach top speeds in excess of 1,400 MPH.

You take off from your base in Thailand in the darkening skies, hit the afterburners, and slowly climb a couple miles up into the night sky and cruise to your designated target area along the Laos/Vietnam border.

Everywhere you look it’s pitch-black. There are no lights below, only dense jungle, rice patties, jagged mountain peaks—and thousands of enemy soldiers who would like nothing better than to shoot you down. With only your cockpit instruments and radar to rely on, it’s like flying through a dark tunnel with no reference points. Your mission is to identify potential enemy targets, attack and mark them with rockets, direct other fighter-bombers to the selected targets, and return safely. Repeat this 155 times, and you will know some of what the Vietnam War was like for Doug LeFever.

Duty, Honor, Country

Paul and Thelma LeFever moved off the farm in 1967 and retired to Page, AZ

where today there is a VFW Post (Lefthand-LeFever Post 9632) named in honor of Doug. After he was declared MIA (missing in action), life was never the same for his Mom and Dad; they had lost the joy of their lives. They are buried in Miltonville Cemetery near Trenton, OH alongside a memorial for Doug.

Doug LeFever was a highly decorated officer. Posthumously promoted to the rank of Major, his awards include: the Bronze Star, Air Medal with 11 Oak Leaf Clusters, Distinguished Flying Cross with Oak Leaf Cluster, Republic of Vietnam Service medal, National Defense medal, and the Purple Heart.

In the end, Doug became what he wanted to be and never had to grow old; his dreams were fulfilled. He was a warrior who loved to fly and believed passionately in the job he was doing, and he did that job well. He was a man blessed with the exceptional skill, courage, and the dedication to keep flying perilous missions into harm’s way night after night—after night.

Doug and the many thousands of other men and women who served with him were young and full of life. They did their duty at a difficult time in an unpopular war where their service was not always valued.

Life goes on. The years roll by, and memory fades. But some things do endure. The contribution that these men and women made through their example and sacrifice should be honored and not forgotten.

So, next time you travel to Washington, DC, make it a point to stop and visit Doug at the Wall. He’s eternally there along with the 58,194 names of his comrades who made the ultimate sacrifice for Country. He’s there among the stilled hopes and dreams of future teachers, farmers, doctors and mechanics that will never be.

And when you find Doug’s name, say a prayer for a young man from this community who accomplished much in his all too short life. Then count your blessings, for you are living the life he wanted to live.